I really appreciated the discussion on my last post, and wanted to clarify some of the issues raised.

My two key points were:

1. The capital gain made from buying a cheap home and upgrading later does not always improve your ability to buy a larger place in the future, and

2. That forgoing life's little luxuries to start a savings plan directed at owning your own home is not always effective. The 'work hard and save' mantra does not work if prices increase faster than your ability to save.

The issues flagged by readers were that

1. I ignored increased wages

2. I ignored the paying down of principle, and

3. I ignored the fact that rents increase in line with CPI while loan repayments do not.

My response is under the fold.

In light of these issues I have posted a spreadsheet here that compares the true investment outcomes of 3 scenarios; buying a home to occupy, buying a home as an investment but renting where you live, and renting and investing the difference between the rent and the cost of home ownership.

The assumptions are outlined at the bottom of the first worksheet, and you can change the scenarios by choosing from the drop down boxes for each of the inputs in black font in the top white boxes. The alternative investment option is that rate of return (combining captial gain and income) from other non-property investment to which the cost savings from renting are directed.

Some scenarios I have run are in the table to the right showing how changing some of the inputs changes the outcome.

The second worksheet shows the calculations, where in each scenario the annual cost is equal to the home ownership option over 30 years. Using this common cost we can overcome the issue of paying down principle, and of increasing wages. Note that rents take about 30 years to reach the current cost of home ownership with compounding 3% annual increases.

What we learn from this exercise is that buying your own home in today's economy is far inferior to buying a home as an investment, or renting and staying out of the property market completely.

Maybe that is a reasonable position, as buying your own home provides some security for which people are willing to pay a premium. But the idea that home ownership is an investment, which is a commonly held belief, is far from an accurate interpretation of the facts.

Thursday, January 28, 2010

Tuesday, January 26, 2010

How not to climb the property ladder

Baby boomers and older generations often cite high expectations and the inability to save as the main hindrance to the younger generations’ ability to buy their own home. They go into great detail about how much it has always been a struggle to buy a home, and that if young people decreased their expectations a bought something small they could work their way up the property ladder.

I am one of those generation Ys looking to buy my own home, and from this perspective, it is not quite that simple.

The argument that if younger generations decreased their expectations, and maybe bought a small apartment now, so that they could somehow work their way up the ‘property ladder’, is entirely misleading.

For example, a young couple buys an apartment for $200,000 in lieu of a $400,000 house they really want based on the contemptuous advice of older generations. They imagine that in 10 years they might be able to sell for $350,000, netting a profit of around $100,000 to spend on a larger home (after transfer costs). The problem is that larger homes have also increased in price by 75%, so that the $400,000 house is now $700,000. Buying that dream home has gone from a $400,000 prospect to a $600,000 prospect even with the apparent advantage of being on the property ladder.

The way to benefit from increasing property prices is to buy multiple investment properties, so that you leverage the benefits beyond your single dwelling needs.

Next, we can look into the arguments about spending a little less on luxuries to get a person into a home buying position. Dining out, gadgets, and holidays all seem to get mentioned. But if we look into it, these relatively small expenses are not the main factor – the main factor is income.

A hypothetical future home buyer might spend $200 per week on dining out, ‘gadgets’ (mobile phones etc), and travel. That’s $10,400 per year – maybe $3,000 on a trip to SE Asia, $2,000 on gadgets, $2,000 on dining out, and the balance for other luxury items. Let’s see what that money could have done if it were funnelled into a property buying strategy.

Assuming a starting point with no savings, this hypothetical person (or couple, or family) can save about $58,000 in 5 years assuming they receive 6% on their savings. If they thought they might one day want to live in a home that currently costs $300,000, by the time they save their $58,000 the home is worth $400,000 (at a 6% price growth rate). They now need $80,000 for their deposit. They continue saving instead of splurging and in another 5 years they have $137,000 saved. The home is now worth $535,000. They have enough for a deposit, but the repayments on their home and associated ownership costs are now around $900/week.

So after ten years of saving, living life without those luxuries that make it so much more enjoyable, they are in no better a position than before.

I’ll leave you with a question. If you bought a home for $100,000 in 1990, and the market his risen so that it is now worth $600,000, how much better off are you?

I am one of those generation Ys looking to buy my own home, and from this perspective, it is not quite that simple.

The argument that if younger generations decreased their expectations, and maybe bought a small apartment now, so that they could somehow work their way up the ‘property ladder’, is entirely misleading.

For example, a young couple buys an apartment for $200,000 in lieu of a $400,000 house they really want based on the contemptuous advice of older generations. They imagine that in 10 years they might be able to sell for $350,000, netting a profit of around $100,000 to spend on a larger home (after transfer costs). The problem is that larger homes have also increased in price by 75%, so that the $400,000 house is now $700,000. Buying that dream home has gone from a $400,000 prospect to a $600,000 prospect even with the apparent advantage of being on the property ladder.

The way to benefit from increasing property prices is to buy multiple investment properties, so that you leverage the benefits beyond your single dwelling needs.

Next, we can look into the arguments about spending a little less on luxuries to get a person into a home buying position. Dining out, gadgets, and holidays all seem to get mentioned. But if we look into it, these relatively small expenses are not the main factor – the main factor is income.

A hypothetical future home buyer might spend $200 per week on dining out, ‘gadgets’ (mobile phones etc), and travel. That’s $10,400 per year – maybe $3,000 on a trip to SE Asia, $2,000 on gadgets, $2,000 on dining out, and the balance for other luxury items. Let’s see what that money could have done if it were funnelled into a property buying strategy.

Assuming a starting point with no savings, this hypothetical person (or couple, or family) can save about $58,000 in 5 years assuming they receive 6% on their savings. If they thought they might one day want to live in a home that currently costs $300,000, by the time they save their $58,000 the home is worth $400,000 (at a 6% price growth rate). They now need $80,000 for their deposit. They continue saving instead of splurging and in another 5 years they have $137,000 saved. The home is now worth $535,000. They have enough for a deposit, but the repayments on their home and associated ownership costs are now around $900/week.

So after ten years of saving, living life without those luxuries that make it so much more enjoyable, they are in no better a position than before.

I’ll leave you with a question. If you bought a home for $100,000 in 1990, and the market his risen so that it is now worth $600,000, how much better off are you?

Sunday, January 24, 2010

How randomness rules our lives and why statistics need discipline

I feel the need to share some of the most interesting insights, and highlight some of my remaining concerns about the nature of randomness and probability. My main reason for caution is because the normally practical and insightful discussion occasionally crosses the boundary between mathematical and statistical insight and plain old common sense. These instances reiterate my stance that statistics need discipline. For now I will put these to one side – topics for future posts. Today I want to share one of the more interesting insights into differentiating luck from skill with some basic probability theory.

If you read any part of this book, make sure it includes the final two chapters which cover human propensity to see patterns where there are none (including confirmation bias and the need to perceive control), how experts are routinely fooled by randomness, how success is often more chance than the result of hard work, how the butterfly effect was accidently discovered by Edward Lorenz in the 1960s (a random event itself), plus much more. The ideas are challenging but presented in terms to make them simple to grasp.

Let’s look at Mlodino’s analysis of the chances that fund manager Bill Miller’s outstanding success at beating the market for 15 consecutive years was simple down to chance.

Now, the chances of Miller’s success being down to simple randomness were widely quoted as 1 in 372,529. But this is the chance that if we had singled him out at the start of his 15 year streak, then followed his performance, and his only, for 15 years. But in reality this did not happen.

In fact this is a startling example of silent evidence. At the beginning of his 15 year ‘winning’ streak there were literally thousands of fund managers in the race to beat the market. It is only in retrospect that we praised Miller and forgot the rest. So the question then becomes what are the chances that one of these thousands of starters will beat the market for 15 consecutive years.

Since he was praised as the only fund manager in the past 40 years to beat the market for so long, Mlodino then calculates the chances that if 1000 fund managers (a huge underestimate) are in the race, that one of them will beat the market for a 15 year period. The new odds; around 75%. That means that it is 75% likely that Miller’s success was simply random chance, and only a 25% chance his skill contributed at all.

I hope this small example helps you to understand the insights offered in The Drunkards walk. The only thing I would have enjoyed more is a reconciliation of determinism and randomness in the final chapter, which only briefly touches on the issue but then brushes it aside. Expect more on randomness and probability in future posts.

Tuesday, January 19, 2010

Helmet law rebound effects and the success of terrorism

I write regularly about rebound effects - those unintended consequences that occur due to behavioural adjustments. I wrote my Master’s thesis on the rebound effects from energy efficient technologies and household energy conservation behaviour (a good summary is here, my thesis is here, a draft paper on household conservation is here, and a draft paper on the effect of government environmental subsidies is here)

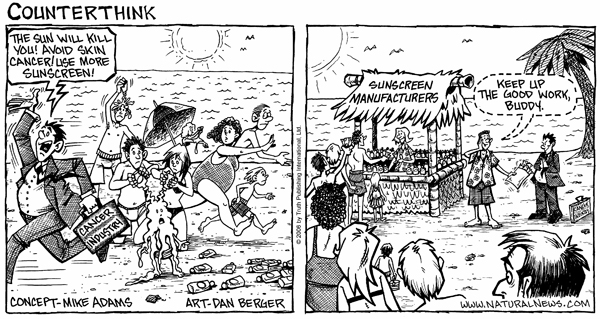

I have written about rebound effects from using photovoltaic panels. The rebound effect from recycling, which enables us to use even more of the raw material we are trying to conserve. Recently, I wrote about the potential rebound effect from sunscreens – because we don’t have the immediate signal of sunburn to tell us that we have had enough sun exposure, we tend to spend more time in the sun.

One area I am particularly adamant that unexplored rebound effects exist is in preventative health care costs – by preventing one disease, we enable people to succumb to other diseases, which have potentially greater treatment costs.

But these sly rebound effects do not end there.

Today I read, in a book on probability and randomness no less, that after the September 11 terrorist attacks the amount of long distance commuting by car increased dramatically due to both fear and forced cancellation of flights. Because of all this extra driving, there were an estimated 1000 extra road deaths than had people continued to fly as their means of transport. The forgotten death toll? A win for terrorists? Or simply unintended consequence caused by human adaptation to circumstance.

Recently a paper was published (see comments and link here) to support the fact that bicycle helmet laws, while reducing cycling fatalities, also reduce the rate of cycling. While the paper does not go into detail on what people are instead doing, we can use this main point to hypothesise a little about what other unintended consequences might arise.

First, the main finding is that helmet laws reduce youth cycling, and subsequent cycling in adult life. For youths, we might suggest that instead of cycling they may be skateboarding or rollerblading instead, without helmets. They may participate in idle activities such as video games, potentially contributing to diseases associated with lack of exercise. There are infinite possibilities about what youth are doing instead, and not all are safer in the short or long run.

This article suggests that when the decline in cycling is factored in, helmet laws result in a net cost to the community. Take special note of the comments. More people suffer severe head injuries from walking, yet there are not helmet laws for that.

Finally, if you are still interested in helmet rebound effects I suggest you have a quick read here.

At the end of the day, if we don’t consider these rebound effects in our policy decisions, nor do we assess the effectiveness of policy in retrospect (why not have a 10 year review or some such thing), then we will continue to make poor decisions for the community as a whole.

Sunday, January 17, 2010

Population growth and the residential property market

I have been asked to develop further my ideas on population growth and residential property. I hope to make it clear that arguments using population growth as a cause of future house price growth are probably misleading.

The first chart (above) shows the rate of population growth (RHS) and the the growth in the ABS capital city price index (LHS). There are two important things to take away from this chart.

1. The rate of population growth can change very rapidly, and extrapolating past trends will always miss changes to this rate.

2. There is no significant relationship between these two figures over the period.

In fact, this chart supports the ideas espoused (for example here and here) that population growth and home prices are simultaneously determined by other factors, such as the health of the economy as a whole. We should really put to rest all arguments centred around population growth and the apparent housing shortage. I always wonder how this population growth occurs without new development anyway? Apart from small changes due to increased occupancy rates, population growth and development reinforce each other.

Even if population growth did strongly explain home price growth, one must imagine that an unexpected future decline in the rate of population growth would lead to price declines. Does that mean that to sustain prices we need to sustain this rate of population growth indefinitely?

Either way you take it, invoking population growth to explain house prices is inherently misleading - why not simply price level and population level?

The second chart (below) show the ABS capital city price index in real terms, and the NSW median household income in real terms. After the 1980s boom, the house price index did not recover its real 1989 peak until 1998 - a period of 9 years with no real capital gain.

What the data misses is that during this 9 year stagnation, the quality of homes, in terms of size and location, was probably improving. A hedonic index (such as the RPdata-Rismark index), had one been around at the time, may have shown and even lower real return, or in effect, a longer period of stagnation.

What is also interesting is the significant change in the ratio of prices to income since the late 1990s, even though Australian mortgage interest rates have been relatively stable since about 1996 (between 6 and 8%).

So what does it all mean?

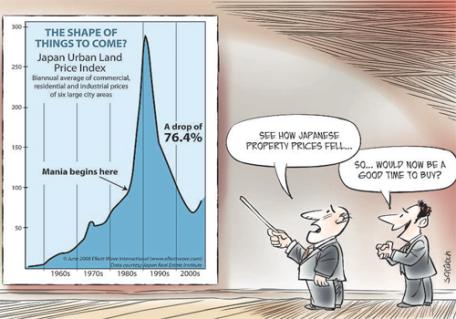

Essentially, we are in for either a long period of stagnation in residential property prices, or, if my predictions of a W shaped financial crisis are correct, potentially a severe short term decline in prices with a very slow recovery. Of course, the RBA has plenty of interest rate ammunition should another crisis precipitate.

Time will tell, but my advice (if you want to know) is that potential home buyers, especially first home buyers, should be in no rush to get into the market.

The first chart (above) shows the rate of population growth (RHS) and the the growth in the ABS capital city price index (LHS). There are two important things to take away from this chart.

1. The rate of population growth can change very rapidly, and extrapolating past trends will always miss changes to this rate.

2. There is no significant relationship between these two figures over the period.

In fact, this chart supports the ideas espoused (for example here and here) that population growth and home prices are simultaneously determined by other factors, such as the health of the economy as a whole. We should really put to rest all arguments centred around population growth and the apparent housing shortage. I always wonder how this population growth occurs without new development anyway? Apart from small changes due to increased occupancy rates, population growth and development reinforce each other.

Even if population growth did strongly explain home price growth, one must imagine that an unexpected future decline in the rate of population growth would lead to price declines. Does that mean that to sustain prices we need to sustain this rate of population growth indefinitely?

Either way you take it, invoking population growth to explain house prices is inherently misleading - why not simply price level and population level?

The second chart (below) show the ABS capital city price index in real terms, and the NSW median household income in real terms. After the 1980s boom, the house price index did not recover its real 1989 peak until 1998 - a period of 9 years with no real capital gain.

What the data misses is that during this 9 year stagnation, the quality of homes, in terms of size and location, was probably improving. A hedonic index (such as the RPdata-Rismark index), had one been around at the time, may have shown and even lower real return, or in effect, a longer period of stagnation.

What is also interesting is the significant change in the ratio of prices to income since the late 1990s, even though Australian mortgage interest rates have been relatively stable since about 1996 (between 6 and 8%).

So what does it all mean?

Essentially, we are in for either a long period of stagnation in residential property prices, or, if my predictions of a W shaped financial crisis are correct, potentially a severe short term decline in prices with a very slow recovery. Of course, the RBA has plenty of interest rate ammunition should another crisis precipitate.

Time will tell, but my advice (if you want to know) is that potential home buyers, especially first home buyers, should be in no rush to get into the market.

Wednesday, January 13, 2010

The land tax remedy

I have made my point about the social benefits of land taxes clearly in the past. I want to now direct the interested reader elsewhere for some informative discussion.

Here is an excellent article discussing land taxes and land price bubbles in an Australian context. More from the same author here, and a plug for his personal blog here (take note of the CPI discussion - I want to discuss that in more detail in the future).

For those who want to digest some of the classic writings on the issue, see Progress and Poverty by Henry George (written in 1879).

Unfortunately there is a powerful political lobby working against such beneficial tax reform. The Property Council of Australia has been pushing for reductions in land taxes, citing any increase in tax revenue from this source as a national embarrassment. Of course, the large increase observed in Queensland (below) is partly due to the extremely low land tax base in 2007/08. Not mention of the scale of the tax, just the increase. Queensland's land tax revenue was just a third of the land tax revenue of NSW in 2007/08.

A little off topic now, but over drinks on the weekend I was talking to a Dutch friend of mine who also happens to be an economist. He is thinking of moving to Australia but is very hesitant due to the exorbitant cost of living here compared to incomes. He recently bought a new apartment in a the 'happening' part of town, and his total costs per month (including loan repayments, body corporate, rates, and his insurance for the home, car and motorbike which are a package) are 800Euro ($1300AUD). That's only $300AUD per week for all those expenses combined! That is below the median rental rate for a 2 bedroom apartment in Brisbane (including new and old stock).

There are a number of reasons for this. In Holland, interest on loans for owner occupied dwellings is tax deductible. The interest rate itself is just 4%.

So if the Dutch average household income is slightly higher than Australia's, and the Dutch have generally less land available, why is owning a home so affordable there? And why is the rate of Dutch home ownership (54%) much lower than Australia's (70%)?

Here is an excellent article discussing land taxes and land price bubbles in an Australian context. More from the same author here, and a plug for his personal blog here (take note of the CPI discussion - I want to discuss that in more detail in the future).

For those who want to digest some of the classic writings on the issue, see Progress and Poverty by Henry George (written in 1879).

Unfortunately there is a powerful political lobby working against such beneficial tax reform. The Property Council of Australia has been pushing for reductions in land taxes, citing any increase in tax revenue from this source as a national embarrassment. Of course, the large increase observed in Queensland (below) is partly due to the extremely low land tax base in 2007/08. Not mention of the scale of the tax, just the increase. Queensland's land tax revenue was just a third of the land tax revenue of NSW in 2007/08.

There are a number of reasons for this. In Holland, interest on loans for owner occupied dwellings is tax deductible. The interest rate itself is just 4%.

So if the Dutch average household income is slightly higher than Australia's, and the Dutch have generally less land available, why is owning a home so affordable there? And why is the rate of Dutch home ownership (54%) much lower than Australia's (70%)?

The sunscreen rebound effect

I’ve just returned from a few days at thebeach with my family. One thing that stands out as a key function of aparent in the summer beach environment is making sure your child avoids gettingsunburnt.

This got me thinking about a world withoutsunscreen. This cheap little cream enables us to withstand sun exposurelike super-humans, avoid painful sunburn, and partake in activities that wouldbe out of the question in a 'no sunscreen' world.

Since sunscreen allows us to tolerate so much more exposure to the sun,is it actually contributing in some way to increased incidence of skincancer? Are the net health benefits of sunscreen

actually much lowerbecause of our change in behaviour? How big is the sunscreen reboundeffect?

There seems to be some acceptance of thesunscreen rebound. This article statesthat “Sunburn may even protect against melanoma - by keeping people outof the sun.”

Again here:

The Australian experience provides thefirst clue. The rise in melanoma has been exceptionally high in Queenslandwhere the medical establishment has long and vigorously promoted the use ofsunscreens. Queensland now has more incidences of melanoma per capita than anyother place. Worldwide, the greatest rise in melanoma has been experienced incountries where chemical sunscreens have been heavily promoted.

And here:

sunscreen use tendsto prolong the amount of time people spend in the sun whilethey are on vacation—and thatonly sunburn modifies the behavior of sun-seekers

And here:

Sunscreens suppress naturalwarnings of overexposure to the sun and allow excessive exposure towavelengths ofsunlight which they do not block.Because sunscreens create a false sense of security, moreeffective measures to reduce sunlight exposure, such as limitingtime spent in the sun or use of hats and clothing, may be ignored.

My experience suggests that all of thesestatements are true to some degree.

If everything was held constant - time inthe sun, covered clothing, etc (notice the decline in hat wearing in the pastfew decades?) - then sunscreen may be quite effective at preventing skincancer. But humans have a tendency to adjust their behaviour to takemaximum advantage of such innovations.

The question that remains is whether thereis still a net health benefit from sunscreen. But due to the plethora ofuncontrollable variable in any longitudinal study, I'm not sure that we willever have definitive statistical evidence for this.

Thursday, January 7, 2010

Are economists cheapskates: A case study

Lately, economists have been copping it from all angles. They have been widely acknowledged as cheapskates, following this Wall Street Journal article.

My personal view is that economists are either; (a) more aware of the satisfaction they derive from various goods, services and activities (they know their utility), or (b) studying economics makes us more aware of which choices provide more satisfaction.

I tend to agree with this point about economists, and myself in particular (from here):

They are cheap in the sense that they need to be convinced of an item's value—and be convinced of the fact that there is no cheaper way of getting that item—before paying up. They hate being wasteful, and they take a cold, scientific approach to maximizing efficiency.

When I consider any purchase I generally think in terms of opportunity cost - what else could I be doing with my time or money that would provide myself and my family greater satisfaction. For example, when I consider a $10 purchase, I weigh up the new item against other things I could have for $10, such as a take away lunch, the ingredients for a home cooked dinner, a book from an online store, fuel for the car to travel about 80kms, and so on. I am even aware that it takes me about 20mins of work to earn this amount after tax. It's not like I think everything through in this way, but I am aware of it, and for items I am on the cusp of purchasing, this awareness helps me to be ruthless in culling unnecessary spending.

So it is with this attitude in mind that I bring your attention back to the photograph above. Next weekend we are heading to Stradbroke Island for a holiday with some friends. Both families are squeezing in to our car to reduce fuel and ferry costs (and you always get great conversation jammed in the car on road trips), so we will need some more space for a few things.

Here's where the economist in me really shines through. Ready made roofracks to suit the car cost between $300 and $400. That's the almost the cost for the whole family holiday, about a weeks rent, a couple of days work, a return airfare to Melbourne and so on.

The value to me is marginal. We will probably only put surfboards up there, maybe a stroller, so the only real difference to the trip will be that I will swim in the mornings for a couple of hours instead of surfing, and may have to carry a child when they are tired.

Instead, I bought some bolts with the correct thread and cut some timber to fit. There you have a $9 roof rack, which in my mind, is equally as functional. Of course there was a couple of hours work involved, but I actually enjoyed a bit of tinkering and couldn't have worked those hours anyway (I was home with my toddler).

By the way, if you read the linked WSJ article, I would not have sent a friend money to hire removalists for a few reasons.

1. I enjoy a bit of heavy lifting now and then.

2. I enjoy the camaraderie when friends pull together to help out.

3. I enjoy the hard earned beers afterwards.

Tuesday, January 5, 2010

GI Joe and the Market for Lemons

The answer is, well, maybe. The reason I sat all the way through is that I thought the movie might redeem itself by having a nice twist at the end, or even a few cheesy lines that I could laugh at. But no.

Considering the number of terrible films made this type of situation is relatively rare. It is easy to get a number of honest reviews to narrow down the quality before watching a film.

In any case, it got me thinking that movie markets are similar to lemon markets because the quality of the good cannot be known in advance. In a true lemon market the quality cannot generally even be known after the good is consumed.

Classic examples of this type of market are for medical services, automotive repairs and second hand goods. Someone with no medical knowledge can see a doctor and be prescribed a treatment, and have no way of knowing whether the prescribed treatment was the most effective of all possible treatments.

For the mechanically inept, that clunking noise can be fixed for a mere $500, but there is no (cheap) way of knowing if it could have been fixed for less once it has been fixed.

For second hand goods, cars in particular, the lemon market makes more intuitive sense. Because the quality of the car cannot be known, people generally assume that a second hand care is of average quality, and pay the price reflective of an average condition car. It is very difficult for those people who fanatically maintain their cars to demonstrate to a prospective buyer that it is far superior to another similar one.

What is more interesting about lemon markets (and the reason I am writing about GI Joe in the first place) is that they were proposed by an insightful commenter here as another reason why your boss often appears incompetent. (Please read the linked article entirely– very interesting)

I tend to agree. In many jobs, especially managerial roles, it is very difficult to evaluate the level of competence of the manager, as opposed to the group as a whole. Also, because the skill set required for each job up the corporate ladder changes, high performance at a lower level job does not imply a solid performance at a higher level.

In our interactive workplace, even the apparent success of one person may be reflected on a whole team, thus encouraging the promotion of others.

The solution to lemons markets is not regulation, but information. New employers do their best but still face the constraints previously mentioned. For second hand car sellers, third party inspections can be worth the money (pay for the buyers own choice of third party check).

Any other markets stand out as potential lemons?

Sunday, January 3, 2010

Economics of work and leisure

I feel like a 20% cut in work has resulted in an 80% improvement in my work satisfaction, rather than merely a 20% boost.

As an economist I really shouldn’t be surprised. Economic theory suggests an optimal work time – there are decreasing marginal benefits to work (in terms of pay), and increasing marginal costs (in terms of time, level of stress, level of frustration etc).

But this experience (and the popularity of this television show) has got me thinking about how the wellbeing of society at large can be improved by working less.

I want to start this analysis with a simple question. Why do so many different jobs, using different skills, different degrees of physical and mental effort, in different locations, all seem to require a single person for about 40hours per week from Monday to Friday, 9am to 5pm, with 4 weeks holiday per year?

My best explanation is that by standardising the work week and adjusting the number of workers to suit, we get two benefits. First, we have a coincidence of work time. Most jobs require interaction with others, whether as part of a manufacturing process, or as part of a service industry. The second benefit is that we have a coincidence of leisure time. We all know that most people will be available on weekends or evenings for shared leisure activities.

Once the five day week is standardised, we find industries which require workers on evenings and weekends having to pay more for labour. The social norm of higher valued time on weekends and evenings, due to coincidence of leisure, then became embodied in legislation.

Surely there is a loss to society from this standardisation? People will value leisure time differently, and value the coincidence of leisure differently? Thus any regulations enforcing a standard work week will be inefficient in the economic use of the term.

This is true. But as is often the case, there is a trade off between economic efficiency and social cohesion. Too much work and leisure coordination can result in problems like in the photo above (see the source for more)

Maybe it is time to move away from the standard week, with more casual and part time positions, as a way to improve efficiency. This is already happening. To maintain social cohesion is a casualised workforce, coincidental leisure time can be achieved by declaring more public holidays (Australia currently has about 11 public holidays – 3 at Easter, 3 for the Christmas/New Year period, leaving just 5 for the rest of the year. Sweden has 16 for example, and Japan 15.) I’m sure there are plenty of politically attractive opportunities to declare more holidays – Sorry Day (13th Feb 2008) is one that stands out.

Given my experience moving to a part time job, the idea of a more flexible workforce and more public holidays stands out as a simple way to improve wellbeing in our society.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)